I had the good fortune recently to listen to a talk delivered by the former CEO/Founder of Jama Software, Eric Winquist. Eric shared with the audience the wins and losses across more than a decade of operation (and what promises to be a lot more success ahead). There was plenty of rich material in his talk, but one nugget, in particular, grabbed me — it was a simple framework for how founders mature:

Maturing founders go from storytelling to the use of lagging indicators and finally to the use of leading indicators.

Or, as I would put it:

First, we lie (mostly to ourselves), then we reflect on the past, and then we try to predict the future.

I’ve written before about the dangers of relying on a story alone. Ask a first-time founder how her/his startup is performing, and you’ll quickly be deluged with anecdotes. She/he will share how the team is forming, the next product feature to be released, and how a specific prospect is close to signing a contract. It will be one story after another. When the tales conclude, you’ll realize you’re not any closer to an answer.

Most first-time CEOs are insecure animals. I know I was. We read articles about unicorns, about $100M+ rounds raised by nonsensical businesses, about legions of pretenders allegedly “killing it,” all while beating away term sheet offers with a stick. Fueled by these articles and social media posts, first-timers feel pressure to inflate their startup’s resume. Suddenly, unpaid pilots become customers. Lightly involved advisors are members of the team. 1099 contractors are dedicated engineers. They think that sounding bigger will help. It will be easier to recruit talent or sell more products or raise money. But to the experienced eye, the Pollyanna routine is all too obvious.

All of these young founders must adapt or perish. Even a well-performing startup won’t stay well-performing for long if it is run solely by stories. When opinions rather than facts drive decision-making, the direction is set by the loudest or most eloquent rather than the most rigorously experimental.

Serious entrepreneurs don’t run startups by sitting around a campfire. They launch companies using milestones, solid frameworks, and metrics. They determine a goal worth achieving, try a bunch of stuff, and then measure fanatically.

What they measure takes two forms — they reflect on the past and (try to) predict the future.

Moving from stories to reflection

At some point, the founder takes honest stock of her/his surroundings. S/he notices that despite all of the compelling stories, the business has not materially changed. The team has not really grown, the number of customers has not risen, and the bank account has continued to dwindle. The CEO must play a multitude of roles — evangelist, salesperson, recruiter, product strategist, financial planner, and more. One of them is Chief Reality Officer. Optimism is fine; naiveté is fatal. So the evolving founder removes their rose-colored HoloLens and examines the facts.

How many customers did they sign?

How much revenue is being generated?

How much has churned?

We call these “lagging indicators,” and they represent what has already happened. Examining these (not at all exhaustive) historical metrics will elicit two probing questions — how have these numbers shifted over time, and how do these numbers compare with what was predicted?

But these numbers however critical to understanding yesterday, offer limited value in predicting tomorrow.

From evaluation to prognostication

Many of us have heard the phrase that you can’t drive a car by adjusting the rearview mirror. The sophisticated founder uses an assortment of tools both to learn from the past and to guide the future. To do so requires one simple inquiry: what metrics predict our lagging indicators?

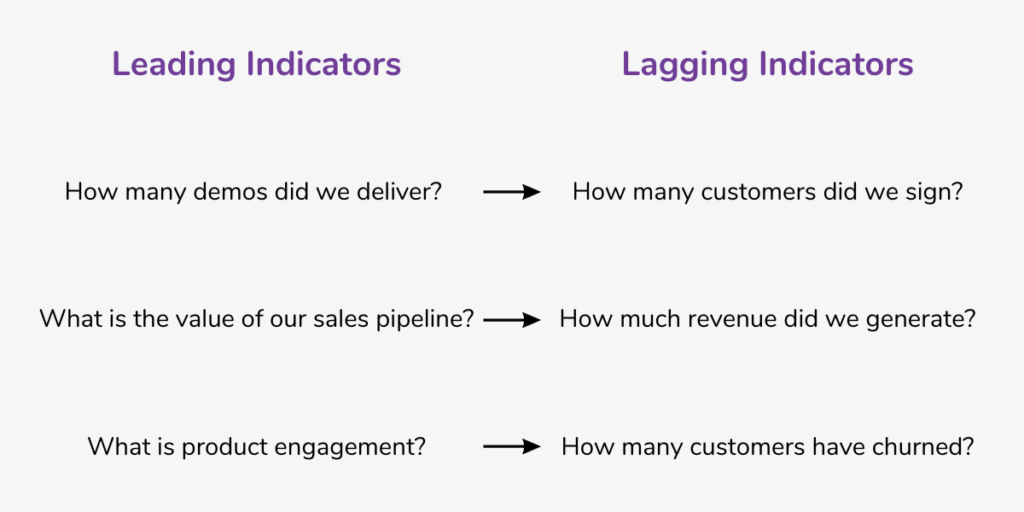

Let’s revisit our prior lagging indicators but now coupled with their leading indicator cousins.

These leading KPIs point toward the future. There are many examples, and often they can be unique to a given business. Active users often are predictive of paying ones. Today’s demo recipients are tomorrow’s customers. Poorly engaged users portend future churn.

For AirBnB, it’s “nights booked”. Facebook focuses on “daily active users.” For YouTube, it’s “watch time.”

Here is a short but not remotely complete list to get your mind working:

- Daily Active Users. (or Weekly or Monthly)

- The number of app installations.

- Total time using the app.

- # of Log-Ins.

- The number of product demos.

- Number of referrals per user. (aka virality)

- Sales pipeline versus revenue plan ratio.

Got it? Now let’s imagine a conversation with a founder at different stages of her/his maturation as a leader.

Storyteller

How is your company performing?

Great! We have an amazing fortune 500 company leaning in and wanting to work with us. We met with them several times, and we have another meeting already on the calendar for next month.

Reflector

How is your company performing?

Last quarter we generated $5,000 in recurring revenue on a total of 4 customers. That is off by 20% from what we had forecasted, and the primary culprit is that our revenue per customer was lower than we anticipated.

Predictor

Last quarter we generated $5,000 in recurring revenue on a total of 4 customers. That is off by 20% from what we had forecasted, and the primary culprit is that our revenue per customer was lower than we anticipated. However, our sales pipeline is ahead of plan. We now are adding ten qualified leads into our funnel every month; our conversion from qualified leads to closed sales is 10%, so given that we currently have 50 top-of-the-funnel leads, I safely can forecast five new accounts equaling an additional $6k of monthly recurring revenue by the end of the first quarter.

Why does all this matter? One reason — speed. If you like the old metaphor that you’re both flying and building your airplane simultaneously (all while low on fuel, mind you), then knowing how to operate the aircraft for maximum effect and efficiency would seem crucial. Lagging indicators let me honestly assess where we’ve been — statistics such as customers, revenue, margin, and profits are what determine valuations and wealth. But the best way to achieve them is by looking at the path ahead, not just by chatting with the passengers or glancing back at the miles already traveled.