For much of the last decade, the lines between fundraising rounds blurred as check sizes and valuations soared. Interest rates were zero, and risky investments were in vogue. Seed, Series-A, and Series-B rounds no longer required distinct performance expectations. The stages lost their meaning.

But rational thinking has (for now) returned. And that means the B round has returned to resume its historic role as the arbiter of operational excellence.

Seed Stage? A compelling story can suffice.

Series A? As long as there is some repeatability, a term sheet will likely follow.

But Series B? The startup better be a high-performing machine.

Easy capital hides a multitude of operational sins. When capital is scarce, only the best operators win.

The Primary Difference Between Raising Series B and All the Rounds That Came Before It.

Across PreSeed, Seed, and Series A, your early investors not only fell in love with you and your startup’s potential, but they knowingly signed up for a decade-long journey together.

Your growth-stage investors? They have a far narrower lens — possibly even as short as just a few years. The relationship is less of a marriage and more of a transaction.

Here’s the elaboration:

When you were raising Series A, you were more story than numbers.

You had very few customers or logos using your product or service. Very few investors on your CAP table. You were in charge of a lean team — not a fully-fledged operation. You needed to demonstrate the potential to entice investors.

Now, you’re more numbers than stories.

Many customers use your product or service. You’ve taken on a long list of investors. You oversee a large operation with lots of moving parts. A compelling tale will no longer impress. Now you need to demonstrate that you have a money-making machine.

At this stage, investors want to be convinced that the only thing holding you back from scaling is capital.

What follows is a mini masterclass on how to prepare for the hardest of venture rounds.

Get ready to show your work.

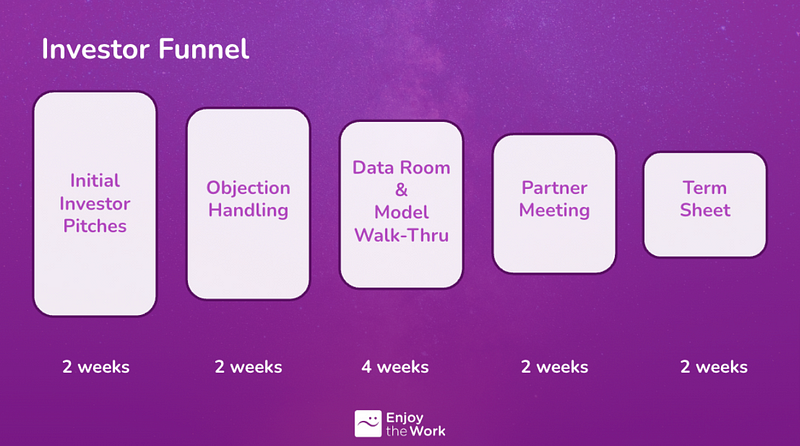

The Series B Fundraising Funnel.

As a startup founder, you live in funnels. You have a sales funnel. You have a marketing funnel. You have a recruiting funnel.

The fundraising motion is simply another funnel to be measured and managed.

If you raised Series A using the Enjoy The Work framework, you’ll recognize the structure. But there are critical differences.

Initial Investor Pitches — Everything Will Feel Faster.

Remember Series A? When investors didn’t know you? When all you had to do was sell them a dream, establish rapport, and show a modicum of repeatable traction to get to the second meeting? Both parties would play coy, slowly getting to know one another before agreeing to a deeper review.

Series B (and later) investors tend to skip the small talk.

Investors may or may not be moved by your story, but they will obsess about your data room. What does that mean for the founder?

Be ready for tough questions from the jump.

The reason is that many of the investors you’ll pitch this round will already be familiar with your business. They’re existing investors. Or colleagues of your board members. Or possibly strategics from within your industry. Or relationships you’ve cultivated since your last round.

These investors know you. They know your business. They know the company’s strengths and soft spots. They’ll have preconceived notions you’ll need to defend, deflect, refute, or accept.

So What Will Those Investors Ask? Preparing for Objection Handling.

Objection handling is Enjoy the Work’s euphemism for Any. Fucking. Question. An. Investor. Asks.

Are they worried about your market size? Objection. Or your leadership team’s experience? Objection. They’re not sure they have the bandwidth to diligence your company right now. Objection. They wonder why your logo contains shades of red rather than shades of blue. Objection.

Step one is to build a list of questions you’re sure to face — You know the questions people ask you about your business, be they investors, potential candidates, board members, or friends over for dinner. Write them all down. Especially write down the ones you PRAY won’t be asked. (Because they will.)

Step two is to write out the answers — And don’t just drop in shorthand bullets. Write out the full answers. And then, practice those answers until your delivery is conversational. Investors respond to mastery. Demonstrate yours.

Why write them out? Three reasons:

- This will allow you to more accurately test different responses.

- Many of the responses you provide will be async, addressing email inquiries. Cut/paste is your friend.

- You won’t be the only person at your company answering these questions; prose promotes consistency. (More on this later.)

What Are Some Examples of Questions Unique to This Stage?

We call them “scaling questions” — inquiries designed to see whether your business is ready to take on and exploit large sums of capital.

How will unit economics and gross margin shift over time?

Venture firms know that, at Series B, your total transaction volume probably doesn’t generate enough revenue to overcome your fixed costs. In fact, they expect you to be burning cash.

They’re not asking you to predict the future with this question; they want you to argue for and against the myriad forces that could alter your unit profitability. If your per-unit economics make sense, profitability is just a matter of time and capital.

How many customers can you deploy concurrently?

Founders often confuse growth with scale. The former means more. The latter means more with less. Provide evidence of leverage (the ability to scale) by showing that you’ve found a way to grow revenue and profitability at a faster rate than expenses.

How many customers can you deploy at a time today? Where does your human and mechanical capacity top out? What are the key investments you need to make to add capacity?

If you were to raise double or triple what you intend, what might you do differently to accelerate?

This question doesn’t necessarily mean your investors want to expand the round size, but it definitely means they want to know if you’d be able to grow faster with more capital.

Have a story ready — what on your product roadmap might you accelerate? Which partnerships might you pursue? Which small competitors might you acquire? Aim for a financial model with easily manipulated assumptions to translate your story to future scenarios.

Who are your competitors, and what is your edge?

Your company is no longer a cute little startup yapping at your competitors’ heels. At Series B, you’re almost grown up. And that means, soon, enemies will begin to notice you.

When they do come after you, will you be ready? Do you have some advantages — maybe your distribution channels, supply chain, or IP — that will allow you to survive the attacks?

Who will be on your team going forward?

For the most part, the people who helped you launch are not the people who can help you scale.

Pausing here to let that sink in.

You haven’t just built a company with these people; you’ve built deep, personal bonds. You care for these people. But investors care less for the history of the business and far more for the future. Is your current leadership team capable of doubling the business? What about tripling? What about 10X?

Your Data Room — The Evidence of Your Answers.

This is the flow to remember. You’ll tell a story. You’ll receive objections. You’ll provide answers. And then you will have to provide proof. Your data room is proof that supports your answers. Any inconsistency equals risk in the investor’s eyes.

If you thought investor diligence was thorough during Series A, buckle up. Investors will be reviewing all aspects of your business. They will ask every question. Examine the evidence you provide. And then seek hidden sources of intel to backchannel you, your team, and your customers.

The Minimum Viable Data Room

Your pitch deck.

Many of Enjoy the Work’s founders have one deck that they use for presenting and another that lives in the data room. The latter is designed to provide more context for people who have not been in the prior meetings.

Your financial model.

Build a model that helps investors understand where the round would take your company and what is on the horizon.

Your financial explainer deck.

During the early stages, you didn’t need one of these. But it’s critical at the growth stage.

This deck tells the story of how your business makes money and explains your sources of growth. It matters because it is likely that, at any given firm, a team of people will be evaluating your company. And several of them won’t attend the initial pitch.

For example, firms often employ a young spreadsheet jockey to examine your financial model. While this person is a master at their craft, they probably don’t know your space, your business, or your growth intentions. Yet they will have a voice when decision time arrives.

This deck is designed to help them understand:

- What your business does, and why.

- The language/glossary of your business.

- The growth drivers.

- The expense drivers.

- How to manipulate the model.

In one to two dead-simple sentences per slide, show people how you make money.

Show them what your revenue drivers are and where growth is coming from. Show them how growth affects the variable and fixed costs of your business.

You have assumptions — about what will drive growth, lower burn rate, and improve margins. Walk through those, starting with the year ahead. Extrapolate a couple of years out, and ground it all in your company’s history. Then explain how that history connects to the future.

And include a glossary. Every company uses jargon that no one outside of the company knows. Define your terms.

Trust me; it’s easier to educate the spreadsheet jockey up front than try to untangle false assumptions after the fact …

Your CAP Table:

Investors are always evaluating a startup across two dimensions:

1) Do I like the company?

2) Do I like the deal?

The CAP table tells them what ownership looks like today and helps them contemplate possible round structures that might work for all parties. A summary version is sufficient. Know that any name or firm listed on the document is a plausible recipient of a backchannel call.

Your sales presentation and demo.

Show investors how you are selling your product or service today. Brief videos of the latter can be effective if well executed. The more mature your business, in terms of revenue and customers, the less the latter is needed.

Your product data.

These are the metrics you obsess about internally. Help investors understand usage and customer habituation. You want to ground them in how you manage the business.

Customer waterfall.

Investors will want to understand acquisition, retention, upsell, and churn over the course of your company’s history. Here’s an example.

Your KPIs.

KPIs don’t just convey your company’s arc. They benchmark its performance against the category leaders you’re looking to mimic. Examples:

- Magic Number — a sales efficiency ratio that compares sales and marketing costs against new ARR generated.

- Cash Payback — a cash efficiency metric indicating how quickly (typically in months) a business recovers the cash outlay required to win/deploy a new account.

- Gross Revenue Retention — gross revenue retention (GRR) rate is the percentage of recurring revenue retained from existing customers, inclusive of downgrades and churn. It does not include up-sells. Anything >90% is admirable.

- Net Revenue Retention — net revenue retention (NRR) rate, also known as net dollar retention (NDR), is the percentage of recurring revenue retained from existing customers, including up-sells, downgrades, and churn. Target metrics depend on customer size, with 90% reasonable for SMBs and 125% for enterprise.

Additional Data Room Artifacts.

There are the basics every startup features. The more veteran founders know to include other elements to solidify their story.

Your FAQs.

Turn all that work you put into answering the questions you prayed no one would ask into a neat, pared-down FAQ. This allows you to frame the narrative on key issues while providing an educational document to all of those who wish to support you behind the scenes (investors, board members, advisors).

Your go-to-market data.

Investors want evidence of efficient channels for attracting, winning, deploying, and supporting customers. That means data illuminating both top (by channel) and bottom of the funnel performance. It’s critical that there is alignment between these metrics and the growth driver assumptions within the financial model.

Your recruiting and people ops win.

If you have something brag-worthy to share, like employee retention, talent acquisition costs, or remarkably high eSAT, do that here.

Your TAM build.

At the Seed stage, it’s a fantasy to imagine how much of a market a startup might win. Scale is ten years away, and so much can shift by the time the startup advances toward maturity.

By Series A, forecasting fidelity improves but not by too much. By Series B, though, there is often a clear line of sight as to what fraction of the market truly is winnable by the startup.

Investors will rigorously inspect:

- How many target customers are in your sector?

- How many already work with a competitor?

- What is the potential revenue per customer?

- Is this a winner-take-all space, or is there room for multiple successes?

- How might your total potential revenue shift as you launch new products and/or raise or lower prices?

Wherever possible, I recommend supporting internal conclusions with analyst reports, public company competitor data, etc.

Your competition.

Who are your enemies, and how are you differentiated? Where are they in the market? How well capitalized are they? Are you fighting head-to-head? If so, why might you win? If not, what’s the fight going to look like when you do?

Investors are sure to seek data that speaks to your win rate vs competition and how often you churn customers to or pull customers away from those in your space.

Your leadership team.

The investors will probe your online profiles and seek out backchannel references. But LinkedIn profiles often lack narrative. So make it easy — share some brief commentary on why your team is suited (uniquely) not only for the sector but for the Series B stage of the startup journey.

Bottom of Funnel: Partner Meetings & Term Sheets.

This part of the funnel remains consistent regardless of stage. The venture firm’s deal lead may invite you to pitch the entire partnership. That meeting is typically a one-hour pitch in front of a large group of managing directors and partners, where perhaps half of the attendees are interested in what you have to say. Whatever lingering objections exist will show up in that room — whether team, TAM, competition, or otherwise.

Ideally, you’ve memorized your FAQ. And your champion prepped you for the contrarians. Following the meeting, you’ll learn one of three outcomes:

1) they are ready to put in a term sheet;

2) they are passing;

3) they have some last bit of homework to do.

If it’s door №1, the venture firm’s deal lead will verbally suggest terms. If you’re disciplined, you’ll resist the urge to negotiate and instead will push for a written term sheet. When faced with a superior negotiating adversary (and trust me, they’re better at this than you), async is your friend. If you reach a signed term sheet, there will be a 30- to 60-day no-shop window for legal diligence and closing before you can celebrate the incoming wires.

Reminders: How to Run a Tight Process

Rehearse like your life depends on it.

Use your board. Use your advisors. Use your colleagues. Take their feedback to heart and pitch them again. And again. Ask them to challenge you so that your objection handling is flawless.

Cluster your meetings.

You should plan to start with 20 to 40 meetings. The better the condition of your business, the fewer meetings you’ll need. If you’re burning a high level of cash and have only modest metrics, then assume a far longer/harder raise or consider seeking an inside bridge before pursuing a new external round.

Take your “least excited about” meetings first so that you can learn from them and update your materials, process, presentation, or all three before the stakes get higher.

Create and communicate scarcity.

Communicate windows versus a hard date. “Right now, I’m taking first meetings; will move to second meetings in two weeks, etc.” The more you can communicate a process, the more investors will believe there is competition and timing to the deal.

Create a private data room for each investor.

I don’t recommend providing 100% of your material to every engaged investor. You want to answer the questions being asked and not more.

The reason is simple — you want to be thorough and honest, but you don’t want to accidentally spur new lines of inquiry. If only one investor wants to fully dig into the scalability of your platform architecture, there is no obligation to share the same with the rest of your pipeline.

Understand pro-rata, and confirm insider support.

Pro-rata is simply the right of certain investors to maintain their ownership percentage during subsequent rounds. Do a pro-forma to estimate the amounts allocated to insiders vs. those available for outsiders. Too little pro-rata interest is a risky signal. Too much, and it can challenge what’s available for the new investor. This part is as much art as math.

Prep insiders for the backchannel.

Your insiders will be back-channeled. No way around this one. And that means new investors are going to reach out to your existing investors, your management team, and even your customers.

Many of the questions they are going to receive are really predictable:

How’s the business doing? How’s the CEO doing? Is this a CEO or a team that can scale? Are you writing a check into this round? Why aren’t you leading this round? What was the plan number this year? And how are they doing vs. that plan?

My simple message to you — get on the same page as your board, key investors, and leadership team. Educate them on the story and the most important objections. If they are surprised by a question, it’s your fault.

As far as prepping your customers, that’ll be no problem for those of you that are high velocity with hundreds of logos. You simply can’t prep that size of the audience, so don’t bother. But for enterprise-focused startups, your client roster is likely far smaller. Be precious about those introductions and push reference calls to the very end of the process. And ensure that those customers know those calls are coming and what questions to expect.

Customer reference calls also are predictable:

- What problem were you trying to solve before choosing to work with <startup>?

- How were you addressing it previously?

- What other companies did you consider before choosing <startup>?

- How has the experience been to date?

- How do you measure success/impact?

- What does <startup> do exceptionally well?

- How could the product/service be improved?

- If you could ask <startup> to expand their offering, what would you tell them to build or add?

Make debt a part of your comprehensive funding strategy.

Debt isn’t talked about as much in venture circles, but it can be a useful, far less-dilutive tool you can use to hit your capital target.

It’s ideal for taking on debt when your balance sheet is rich, so consider it coincident with an equity round. The smaller the ratio of debt to equity and the greater the cash flows of the business, the more comfortable the board likely will be with the tactic. Why is that important? Debt is at the top of the stack, ahead of even preferred shareholders. So this tactic typically requires formal consent.

I’ll share that during times of growth and easy access to capital, using debt to accelerate is a common strategy. However, during more volatile or difficult business environments, debt can actually hasten a startup’s demise. So tread carefully.

Diligence is a two-way street.

Do you know what type of board member you might be getting? Is the investor hands-on? Helpful beyond writing a check? Have you spoken to several past founders with direct experience in the firm? Or have you asked about how they handle reserves? Have you asked your current investors and board members to gather intel? Don’t be shy. You likely do a lot of homework before hiring a key exec. Please apply similar rigor when bringing on someone who can fire you.

Summary Thoughts

The seed stage requires a story, a massive market, and a modicum of evidence that what you’re building is gaining speed. Series-A investors, meanwhile, ask for a repeatable machine. Your business must consistently win and support (evangelical) early adopters. Series B is the first raise in which investors are betting on evidence, not just promise, that you might win the market.

I know recent years have led to confusion over what it means to be a Series-B company. I’m not alone in positing that startup cemeteries are about to be full of companies that raised the mythical B while lacking much of what I described in this article. When money was cheap, investor standards dropped.

And when capital is scarce, only the great operators will survive. Series B will no longer simply be the next round-up for legions of startups. It will be the great separator between those founders demonstrably on a path to market dominance and those who hope that a modest exit will provide a reasonable return to shareholders. At least, that’s how a banker would think about it…